It’s possible that I met Ascher once before she came to live with me. I went to a summer party at a trinity-style house in Fishtown–my first party in Philadelphia, surrounded by near strangers who knew each other. I remember feeling overwhelmed by the social intensity, the wet heat of August, and whatever it was we were drinking outside in the yard. At one point, the host brought out a box of squirming kittens. I hovered over the box and crowed. Kittens! Familiar, adorable, the opposite of loneliness. This is the only thing I remember from that party, aside from the sweaty socially anxious feeling.

The kittens were Ascher’s. I don’t think she was in the box with them. She was likely hidden, anxious. When I first met her, she was suspicious of strangers and hated loud noises.

So it’s more plausible that I first saw her as a soft gray blur from a carrier to a large chest of drawers in my studio apartment. She stayed under there for several days, while her more outgoing sister came and went. They moved into my shoebox of a studio apartment in a temporary-turned-permanent arrangement when their previous carer moved away.

In time, she cautiously started playing–in the dark, mainly, or under the bed. She looked startled when observed. Sometime in that first year, she jumped onto my lap and immediately crouched in uncertainty. What to do, once there? Who could get comfortable in such an unstable environment?

The three of us moved out of the studio into a long, narrow rowhome apartment, and then another. Ascher’s personality emerged, complete and definite. She was shy, but she liked some people more than others, and she would show her preference immediately. She was oddly expressive with her back feet; she would stretch her back legs out straight without moving the rest of her body, and sometimes she would prop them up on me like an ottomon. She liked to sit in the very center of squares: a pillow, a couch cushion, the rainbow afghan my grandmother crocheted, the T-shirt quilt my mother sewed. If her sister was near, they often adopted the same pose but mirrored.

She loved toys. Almost all of my early memories of Ascher involve her bringing me something to play with. Fuzzy toy mice and shiny toy fish. A marvelous bouncing ball called a Zany that would careen in unpredictable directions if I threw it on uncarpeted floor. A motorized toy mouse that she washed in her water dish and dropped, sopping wet, by my office chair. Random things that she found around the house: twists of paper, a memory stick. She was happy to chase laser pointers and toys on strings with her sister–although, if Ascher caught the quarry, it was game over. She played for keeps.

Like a raccoon, she was attracted to shiny objects. She stole pens, paperclips. Once she picked up my nail trimmers in her teeth and ran, although this may have been an objection to having the tips of her long curved claws clipped. Once I took her to the emergency vet for a limp, and her X-ray revealed a sewing needle threaded among the fine bones of her paw. (She recovered quickly, with the help of chicken-flavored painkillers that she rather enjoyed.)

She hated surprises. It took her several years of living with me before she tried jumping on the kitchen table, but she would usually jump right back down–there were other things on the table, things she couldn’t see from the ground, so she was startled every time. If she was brave enough to hang out in a room with my friends, she would flee if we burst into laughter. When we moved into the house with a will of its own, she put herself in the storage compartment of my futon and would not move out for several days.

But not only did she adjust every time we moved, she eventually softened and relaxed. She got open-minded about people and parties. Although Anise remained alert and vigilant into her senior years, Ascher was content to observe; in the vermin-infested house with a will of its own, she watched spiders and beetles with great interest, but no predatory instinct. My friends joked that she retired.

Ascher got old. She went from being a cat who never got sick or injured to a cat who needed prescription food and medication and regular checkups. I mixed a joint supplement and an immune booster into her food. She wore a glucose monitor for a few weeks. At night, she wandered and hollered like a lost ghost until I started giving her CBD oil before bed, which seemed to help her have a calmer night. By day, she seemed content enough. She lay in sunbeams and watched pigeons. She ate whenever she was hungry. She still shoved her head into your hand if you stooped to pet her.

One of our last good days together happened to coincide with a dinner party. I’m not sure whether Ascher was already positioned on the couch when guests started arriving or if she came down the stairs in her slow seesawing gait, first the front legs, then the back legs, one step at a time. In any case, she was soon parading around on the floor, stretching her atrophied hindquarters to be admired. She herded guests to the couch, bleating her officious meow, and then ascended–always an effortful maneuver for her at that age, but it’s where she wanted to be. Showered with attention, she dozed off and remained contentedly on her seat, even after we were all at the table and crackling with laughter.

After dinner, we shifted back to the couch to play games, and Ascher rearranged herself so her arthritic hips and feet were pushed up against someone’s warm backside. She sank into a deep, satisfied sleep then, only waking when I gently stroked her to see if she wanted her nightly CBD oil. (She did.)

After everyone left, Ascher remained comfortably reclined while I washed dishes and packed up leftovers. Then she stood up, shook herself, and sneezed a spray of bright red droplets across the blue seat cover.

I can say that her last few months were as good as I could make them. She ate well, played often, and bustled (slowly) up and down the stairs. I kept two sets of pet steps by the bed so she could ascend whenever she wanted. She liked to sleep right up against one of the pillows, facing me. head on the pillow, feet under a sheet or blanket. Sometimes when I was waking or falling asleep, I would turn to face her and stroke her head, she would reach out and pat me in a grandmotherly way. Sometimes she would touch my forehead and then leave her paw there, gentle but heavy.

She had more vet visits than she cared for, although she didn’t mind the Gabapentin nap afterward. One of these exams knocked free a 6-centimeter tumor that had been clogging her upper nasal passages. She was sore for a day or two, but then suddenly her energy and appetite sprang back. She could breathe better, and food tasted very good to her. She ate with gusto.

But the tumor was not benign, and in a few months she began having fewer good days. Running humidifers upstairs helped ease her breathing, but she still struggled. Many nights, her breath would become ragged and loud enough to wake me. She would eat only if I held the plate right up to her nose, and turned it slowly while she nibbled her way around the edges.

I had more time and more choices than I had when arranging Anise‘s end of life care. After a week of not very good days, I scheduled a vet to come to our house. I still wasn’t sure it was the right choice. Two days later, a viscous fluid began seeping from her nostrils. Then I realized that that the time would never feel right to me, but it had come nonetheless.

Ascher was 19 years and eight months old when I held her for the last time, wiped her face, brushed her unkempt fur, and let a stranger carry her away.

It has been an entire year since I said goodbye to Ascher. I still see her from time to time, coming up the stairs as I pass or, more often, reclining on my bed in a sunbeam. When my mom visited, she saw her there too. My mom has always found comfort in the idea of loved ones visiting from the afterlife. But for me, if anything, these manifestations disprove the possibility of ghosts. It makes sense to me that my neurons misfire from time to time, following the paths formed by years of sharing a space together. The first time I perceived Ascher’s presence was just a few hours after the vet carried her still body away: I was sitting upstairs, staring dumbly into space, when I heard her take a long ragged breath from her bed down the hall. Like she was still having trouble breathing. If she could choose to come back, that is not the way she would have chosen.

When Anise died and our small tribe became a pair, it was different; I still had Ascher to look after, and she needed a lot of care. Now it is just me, most of the time, although I’ve kept the occasional boarder for a week or two while their family is away, and I’ve been fostering a friendly stray for nearly two months. I like having these creatures in the house, although they underscore how unready I am to make another commitment for life.

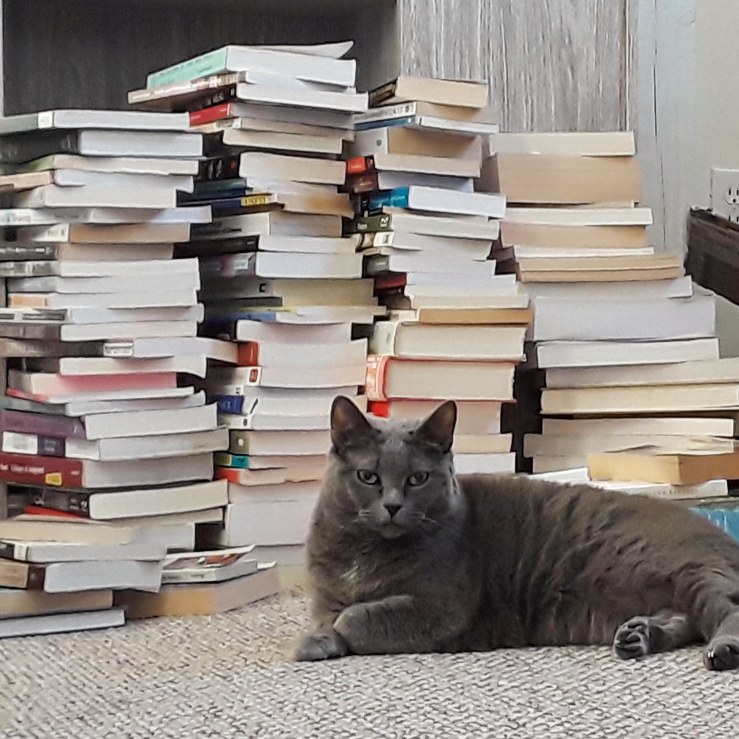

Meanwhile, I still find myself wanting to pile up and treasure the details of her long life. Ascher once stole a plum from a bowl on my table, and rolled it around like a ball. Ascher loved to chew on the bristles of my straw broom. Ascher used to run and hide from the vaccuum cleaner, but when she got old, she simply turned away and buried her face in a pillow until I finished cleaning. Ascher made the nurses pet her while she waited for me to pick her up from the hospital. Ascher used to stare when she wanted something, intent and patient, just waiting for you to do the right thing and give it to her. My beautiful old girl. Ascher loved her sister, and she loved me, and I count myself among the most fortunate of creatures. There will never be another like her.