In spring 2023, I took an 8-week course titled Introduction to Disaster Management. I’ve thought about the material from that course very frequently ever since–especially during the summer, when we see more frequent fires, floods, hurricanes, and heat waves. I’ve struggled to summarize and share this information, though. The textbook we used for the course was Phillips, B. D., Neal, D. M., & Webb, G. R. (2022). Introduction to Emergency Management and Disaster Science (3rd ed.), which was extremely readable and well-organized as textbooks go, but wide-ranging and packed with sources, so it’s difficult to break down into smaller bites.

This is my attempt to make those smaller bites available to peers–at least, the parts of the course that stuck with me the most after the course. All of the below info comes from Introduction to Emergency Management and Disaster Science, unless otherwise cited. I hope you find the information useful, reassuring, or at least a good starting point for your own research.

The term “natural disaster” is misleading

According to the received definition in the field of disaster management,

Disasters are actual or threatened accidental or uncontrollable events that are concentrated in time and space, in which a society (or a relatively self-sufficient subdivision of society) undergoes severe danger, and incurs such losses to its members and physical appurtenances that the social structure is disrupted and the fulfillment of all or some of the essential functions of the society, or its subdivision, is prevented.

Disaster management professionals also distinguish between scale. An emergency is part of everyday life; house fires, heart attacks, and car accidents may be catastrophic for individuals, but a community’s resources can typically meet the emergency response needs of these events. A disaster exceeds a community’s ability to respond; outside help is need. A catastrophe impacts or destroys almost all of an area’s buildings and infrastructure, which impedes emergency response organizations at the local, regional, and sometimes federal level.

Disasters, in other words, are inherently social events. People may live and work alongside hazards every day; we live near hurricane-prone coasts, tornado alleys, flooding rivers, and regions that experience extreme heat and cold. It’s human behavior that turns a hazard into an emergency or even a disaster: where we live, how we build our infrastructure, whether we know what to do and how to protect ourselves when a hazard shifts from potential to imminent. Some go so far as to say that there are no such thing as natural disasters.

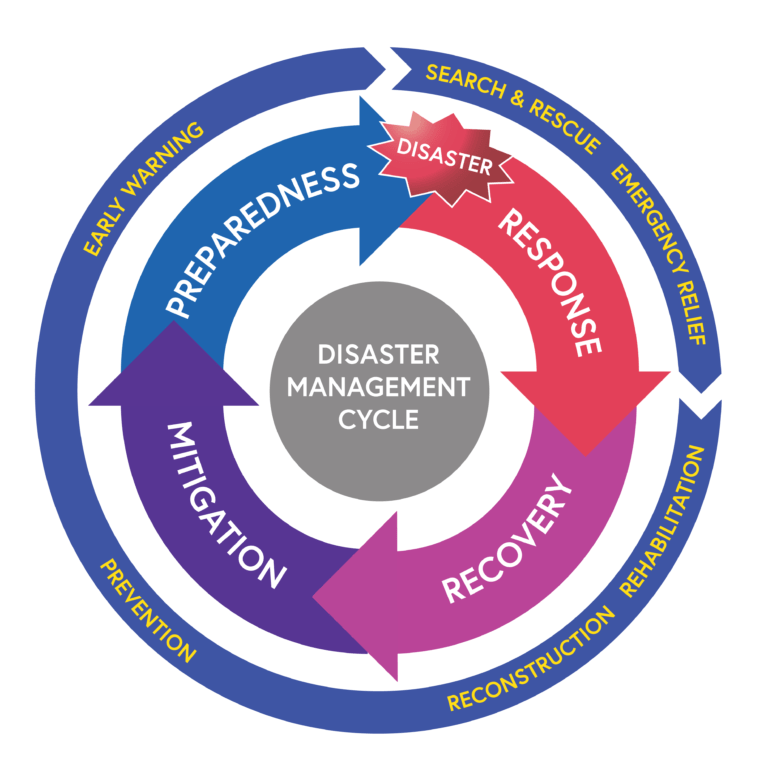

The disaster management cycle

The disaster management cycle has four phases, excluding the disaster or crisis itself:

- Mitigation, which includes activities that eliminate or reduce the probability of a disaster occurring.

- Structural mitigation refers to physical changes to the built environment to lessen disaster impacts. For example, levees, elevation, improved building codes, retrofitting.

- Nonstructural mitigation refers to efforts that change human behavior. For example, relocating populations in hazardous areas; land-use planning that limits building in hazardous areas; building code development and enforcement that determines what can be built in hazardous areas, and how.

- Preparedness, which includes activities that are necessary when mitigation can’t prevent disasters. Preparedness may include planning, acquiring equipment (such as PPE), training (e.g. tornado drills), education, and evaluating past disasters to apply lessons for improvement.

- Response refers to the activities following an emergency or disaster. Disaster response may be provided by:

- established organizations performing their regular tasks (e.g. police and fire departments)

- expanding organizations that add staff and volunteers to meet disaster need (e.g. the Red Cross)

- extending organizations that have an established structure but take on new tasks in the aftermath of disaster (e.g. a construction company helping with debris removal)

- emergent organizations that didn’t exist before the disaster, and perform new tasks (e.g. a search and rescue crew)

- Recovery includes activities that continue until all systems return to normal.

- Short-term recovery may entail the restoration of key utilities and placing people in temporary housing.

- Long-term recovery determines when and how to rebuild–and whether reconstruction will restore or return damaged structures to the way they were, versus rehabilitate or improve the construction in anticipation of future disasters.

Activities in one phase can help support another phase. For example, disaster mitigation can be costly, but investing in structural and nonstructual mitigation in the long term can reduce the cost of disaster recovery. Spending time on emergency education and planning means more people can keep themselves safe in the event of a disaster, which can minimize harm and loss in the response phase.

The way we depict disasters in media–fiction and nonfiction–is also frequently misleading

Here are a few debunked disaster myths and related insights from sociological research. Many of these are attributed to Response to Disaster: Fact Versus Fiction and Its Perpetuation by Henry W. Fischer.

- Panic flight is not a common reaction to disasters. People who evacuate from disasters are not fleeing in panic; they are acting rationally. In many scenarios, people take the time to help one another get out.

- Although some people fear looting enough to refuse evacuation, and in some cases the national guard is activated to prevent looting, it isn’t that common. In post-disaster situations, crime declines.

- Price gouging, or the intentional increase in the cost of items, rarely occurs. If it does, it is usually done by outside vendors.

- We often see images of disaster victims in shock, walking in circles, too out of it to know what to do. In real life, disaster survivors usually respond and provide aid to one another first, before outside help comes.

- There is a myth that public shelters get overcrowded with evacuees, but they are underused. People would rather go to family and friends, or not leave at all.

- People frequently overestimate damage and death from disasters. Sometimes this is intentional (to get federal support, for example) and sometimes this is media sensationalizing.

- Despite the popularity of clothing and food drives, the best form of emergency assistance is always to send money.

You and your household should have an emergency preparedness plan

If you need to evacuate your home, where would you go? Who would you need to call? If you have to shelter in place for a few days, would you have enough supplies? The best time to answer these questions is well in advance of any emergency or need–and then to revisit your plan periodically to make sure it is up to date.

Ready.gov offers resources for emergency planning, as do the American Red Cross and FEMA. Some suggestions drawn from these sources:

- Analyze the possible types of hazards that present risks where you live.

- Some examples that may or may not apply to you: floods, flash floods, fires, hurricanes, tornadoes, mudslides, extreme heat, extreme cold.

- Review how each member of your household receives emergency alerts and warnings for hazards.

- My city has ReadyPhiladelphia, a text alert system for updates about floods, air quality, and other hazards.

- Review any special requirements for members of your household, including seniors, pets, and service animals

- What medications, mobility aids, dietary needs, documents, etc. might each member require?

- Determine a shelter in place procedure.

- Lay out an evacuation plan and route.

- Determine a location to meet if household members become separated during an event.

- Establish an appropriate shelter in place procedure and practice it before an event.

- Ensure that each household member has contact information for other members.

- Ready.gov recommends text messages for communication, as they take less bandwidth than phone calls.

- Have an emergency charging option for your phone.

- Put together kits to both shelter in place and to evacuate.

- Consider your pets, sheltering or evacuating with them, and their food, water, and medication needs.

- Practice your plan once or twice a year.

What goes in your emergency kit?

From Ready.gov:

- Water (one gallon per person per day for several days, for drinking and sanitation)

- Food (at least a several-day supply of non-perishable food)

- Battery-powered or hand crank radio and a NOAA Weather Radio with tone alert

- Flashlight

- First aid kit

- Extra batteries

- Whistle (to signal for help)

- Dust mask (to help filter contaminated air)

- Plastic sheeting, scissors and duct tape (to shelter in place)

- Moist towelettes, garbage bags and plastic ties (for personal sanitation)

- Wrench or pliers (to turn off utilities)

- Manual can opener (for food)

- Local maps

- Cell phone with chargers and a backup battery

Additional items to consider:

- Soap, hand sanitizer and disinfecting wipes to disinfect surfaces

- Prescription medications

- Non-prescription medications such as pain relievers, anti-diarrhea medication, antacids or laxatives

- Prescription eyeglasses and contact lens solution

- Infant formula, bottles, diapers, wipes and diaper rash cream

- Pet food and extra water for your pet

- Cash or traveler’s checks

- Important family documents such as copies of insurance policies, identification and bank account records saved electronically or in a waterproof, portable container

- Sleeping bag or warm blanket for each person

- Complete change of clothing appropriate for your climate and sturdy shoes

- Fire extinguisher

- Matches in a waterproof container

- Feminine supplies and personal hygiene items

- Mess kits, paper cups, plates, paper towels and plastic utensils

- Paper and pencil

- Books, games, puzzles or other activities for children